Soy received a major shout out from Zhubi-Bakija et al.,1 in the form of a position paper written on behalf of the International Lipid Expert Panel, which is comprised of nearly 100 experts from around the world. The panel was charged with elucidating the impact of animal vs vegetable protein on cardiometabolic risk factors. The panel also provided recommendations on the protein content of the optimal diet.

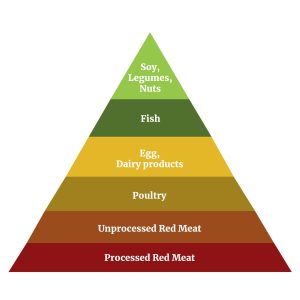

The position paper included a “protein pyramid,” which, as shown below, placed soy protein at the very top. Soy and/or its constituent isoflavones were seen as improving lipid levels (decreasing total cholesterol, LDL-cholesterol, and VLDL-cholesterol and triglycerides), exerting antioxidant effects, reducing pancreatic islet b cell loss and decreasing blood glucose levels and exerting anti-inflammatory and anti-hypertensive effects.

The panel concluded that red meat increases cardiovascular disease risk. As such, replacement of red meat with fish, poultry and dairy protein was seen as reducing cardiovascular disease (CVD) risk, although not as much as would be the case if red meat was replaced with plant protein such as soy and nuts.

With respect to soy, Zhubi-Bakija et al.1 acknowledged that “due to the fact that it is impossible to investigate the effect of dietary proteins only on health outcomes, we still cannot exclude the possibility that their favorable effects in lowering CVD risk could be due to isoflavones or unsaturated fats (or other dietary components).” From an academic perspective, not being able to identify the component(s) of a food responsible for a given health outcome is problematic, especially when adopting a reductionist approach, as is so often the case. But from public health perspective, that is not a problem, as people eat foods, not ingredients. That there are potentially multiple components of soyfoods, or any other food for that matter, that can potentially improve health outcomes, is simply more reason to add that food to your diet.

For some time now, the trend in nutrition and public health has been to move away from basing dietary recommendations on nutrients to basing them on foods and overall dietary patterns.2 It is much easier to identify dietary patterns that promote health than it is to identify specific nutrients, and even foods, that do so. This may be true in part because of food synergy, the notion that foods interact with one another in ways that are not predicted by the collective actions of individual foods.2 The need for transitioning away from nutrients and toward dietary patterns is exemplified by evidence showing that despite their high saturated fat content, full-fat dairy foods are not necessarily associated with an increased risk of CVD.3

Finally, the cardiometabolic advantages of soyfoods has been called into question recently because of the pending decision by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration about whether to modify the existing heart health claim for soyfoods, which is based on the cholesterol-lowering effects of soy protein. There is speculation that if the existing unqualified claim is revoked, it will be replaced by a strongly worded qualified claim. Regardless of the FDA’s decision, the position paper written on behalf of the International Lipid Expert Panel emphasizes that soyfoods warrant a role in heart-healthful diets.

Source: Zhubi-Bakija et al.,1 position paper, International Lipid Expert Panel, Clin Nutr, 2020.

References

- Zhubi-Bakija F, Bajraktari G, Bytyci I, et al. The impact of type of dietary protein, animal versus vegetable, in modifying cardiometabolic risk factors: A position paper from the International Lipid Expert Panel (ILEP). Clin Nutr. 2020.

- Messina M, Lampe JW, Birt DF, et al. Reductionism and the narrowing nutrition perspective: time for reevaluation and emphasis on food synergy. J Am Diet Assoc. 2001;101(12):1416-9.

- Hirahatake KM, Astrup A, Hill JO, et al. Potential cardiometabolic health benefits of full-fat dairy: The evidence base. Adv Nutr. 2020.